| |

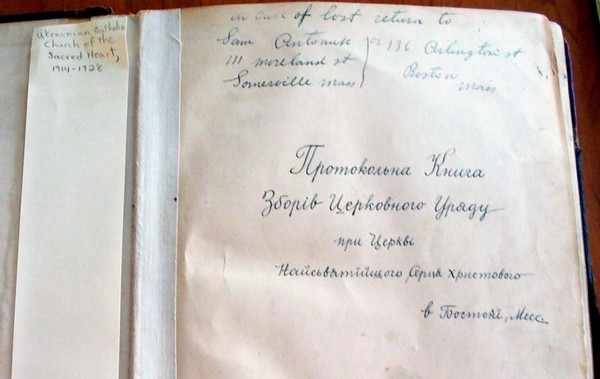

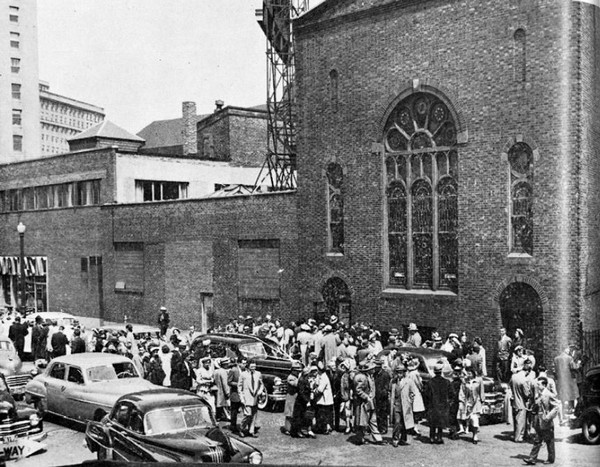

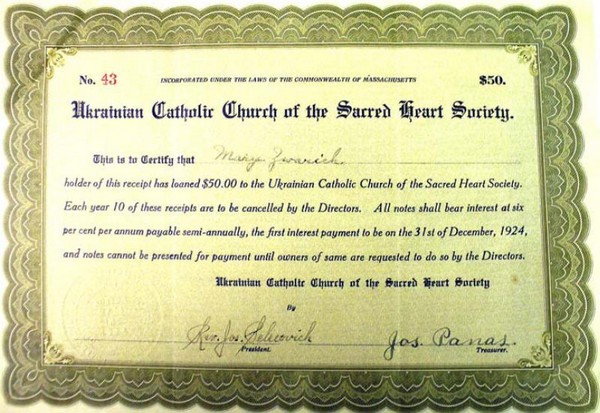

“Protokol’na Knyha,” book containing minutes of the Sacred Heart Church, 1917-1928 Boston has always been a city on a hill and has acted as a magnet drawing people of many origins to the opportunities it offers. First came the Puritan dissenters, followed later by the French Huguenots. The Irish and the Germans came next, and then in the latter part of the 19th century groups representing all the countries and nationalities of southern and eastern Europe began to stream into the city. Among the latter groups were the Ukrainians. They were abandoning their homeland in large numbers at that time because of poor economic conditions and because of the discrimination they faced within the Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires. They came to Boston because its industry held out the promise of good living conditions and its reputation seemed to indicate tolerance. Although the first immigrants came immediately after the Civil War, large-scale immigration did not occur until the late 1880s. The first immigrants were compelled to seek work immediately and as a result had little time for any organized activities. Ukrainians tended to settle near their places of employment, and within a short period of time there were sizable groups living in the North End (many worked digging the harbor tunnels connecting the North End with East Boston), near the mills of the South End and Hyde Park, and near the factories of Norwood. A cohesive group also began to develop in the West End, and a little later there were major settlements in Roxbury. There are some indications in the records of the chancery of the Roman Catholic archdiocese of Boston that an itinerant Greek-Catholic priest sought and was given permission to say a liturgy for Slavic/Ruthenian immigrants in the fall of 1890. Most of the early Ukrainian immigrants were Catholic, and because no regular Ukrainian-rite services were available to them, many, particularly those from the Lemko regions of Western Ukraine, joined with their Polish neighbors to establish Our Lady of Czestochowa Polish parish in South Boston and St. Adalbert Polish parish in Hyde Park. In 1894, however, a group of fifteen young men came together and formed the Ss. Peter and Paul Ukrainian Catholic Brotherhood. The purpose of the Brotherhood was to work toward establishing a Catholic church of the Ukrainian rite in Boston and to preserve and foster Ukrainian culture. Early in 1895 their work bore fruit, and Father Nestor Dmytriv celebrated the liturgy for them according to the Ukrainian rite in St. Leonard’s Italian Catholic Church on Hanover Street in the North End. Ukrainian Catholics did not have their own ecclesiastic structure and fell under the jurisdiction of the local Latin-rite Roman Catholic ordinary (bishop, archbishop, or cardinal) until 1914. On September 13, 1895, Father Eugene Volkay petitioned and received faculties from Archbishop John Williams of Boston to work among the Ukrainians of the city as his vicar. Father Volkay was the pastor of a church in Brooklyn, New York, and yet made frequent trips to Boston to tend to the needs of his flock. In 1897, a branch of the Prosvita (Enlightenment) Society was established in the North End, and a reading room and a discussion club were started. Shortly after the turn of the century, Ukrainian immigration to Boston picked up considerably, and social and cultural activism stirred within the community. The Ss. Peter and Paul Brotherhood became much more active and began agitating for a permanent pastor and a separate church building. The number of visits by Father Volkay increased from once to twice a month, and the Society appointed a committee to raise funds for the expenses of the community, to pay rent and utilities at St. Leonard’s, and to set up a permanent parish in Boston. Every section of the city had collectors assigned to visit each known Ukrainian and to solicit funds. At this time, for example, Hyde Park had some three hundred known Ukrainian families and six collectors. In August of 1907, the Holy See appointed Father Soter Ortynsky, D.D. bishop for all Ukrainian Catholics in the United States. Soon after his installation in Philadelphia, he designated Boston as the seat of a new Eastern-rite New England Deanery and appointed Father Oleksa Pavlak of New Haven, Connecticut, as the first dean. Due to the shortage of Ukrainian priests, however, Father Pavlak was not able to leave New Haven and could come to Boston only once a month for services. These services were held in St. Leonard's Italian Church, and they continued there until the parish bought its own place of worship.  St. Leonard's Church, Boston In 1909, a new branch of the Prosvita Society was established, and in 1910, the Taras Shevchenko Library was opened on Auburn Street. At the same time a permanent residence was procured for the priest on Beacon Street. Among the most active members of the Ukrainian Catholic parish at this time were: Ivan Zinkowsky, Ilya Kulyk, Petro Onulak, Andrew Yavoriwsky, Ivan Kalyta, Pavlo Kudryk, Ivan Chrusch, and Stephen Zaborski. Not only did the local community strive to create a life for itself in Boston, but it attempted to ameliorate conditions in Galicia and Ukraine as well. Money was sent in support of the Ukrainian Private Educational System and the Prosvita Society. Several community centers were built in Galicia partially from the funds sent from Boston. On August 2, 1914, a Presbyterian church was purchased on Ferdinand Street (now Arlington Street) for the sum of $27,000 and converted for use as a Ukrainian Catholic church. It was named for the Sacred Heart of Jesus. This was done at a time when the average Ukrainian was earning less than $3.00 a week for 48 hours of work. Shortly after the church was purchased, a Ukrainian parochial school was established. At first it met once a week, but shortly thereafter sessions were increased to three times a week. Among the subjects taught were religion, Ukrainian grammar and literature, geography, folklore, mathematics, music, and dance. Within a year of the establishment of the Ukrainian Catholic parish in the South End, members of the Russian Orthodox mission, financed by the tsarist government, began to agitate parish members, and under the influence of a former Ukrainian Catholic priest, a number of them broke away and founded the Holy Trinity “Russian Orthodox Greek-Catholic” parish in Roxbury. However, the bulk of the parish remained intact and continued to expand until World War I completely cut off all avenues of immigration. At that time there were about 4,000 Ukrainians living within Boston, and the vast majority belonged to the Ukrainian Catholic parish.  Sacred Heart Church on Ferdinand St. (present-day Arlington St.) During the war, Ukrainians followed developments in Europe very closely. They actively supported their kinsmen at home and sent money, food, medicine, and clothing to the war-ravaged lands. As the Austro-Hungarian and Russian monarchies dissolved, and the Ukrainian and Western Ukrainian (Galician) Republics were formed, the Boston community stepped up its aid. Since most of the Boston Ukrainians came from Galicia and Transcarpathia, developments in the Western Ukrainian National Republic were of special interest to them. In 1918, Dr. Luka Myshuha, a special envoy of the Western Ukrainian Republic, visited Boston seeking support for his beleaguered country. The local community conducted an intensive fundraising campaign and also moved to secure an audience for Dr. Myshuha with President Woodrow Wilson. The cultural and social life of the community flourished during and after the war years. A dramatic society and a choral group were founded. A marching band and an orchestra were also formed. Branches of the Ukrainian National Association, the Providence Association of Ukrainian Catholics, the Zaporozhka Sich Benefit Society, the Ukrainian Workingmen's Association, and the Ukrainian Boston Benefit Society were all organized under parish auspices. The Women's Society of the Holy Virgin Mary and the Boston Branch of the Ukrainian National Women’s League of America came into being and provided many services for the entire community. The Prosvita Society gained many new members, and the library and the school continued to expand. In 1918, St. Nicholas Ukrainian Bukovinian Orthodox Church was established in Cambridge. In 1924, a large number of Sacred Heart parishioners became disenchanted with the current pastor and withheld their financial support from the parish. After a few months the parish could no longer meet its monthly mortgage payments and was in danger of foreclosure and of losing the church building. The parish committee then wrote to Father Peter Poniatyshyn, the administrator of the Ukrainian Catholic diocese in the United States, asking for permission to take over the finances of the parish and to reconstitute the parish as a society in which the members held shares. They explained that this was the only way for them to raise money to continue paying the mortgage. Father Poniatyshyn agreed and turned over the church deed to the new society. Most parishioners took shares and the building was saved.  Notes Sold by the Sacred Heart Society of the Ukrainian Catholic Church In 1927, reacting to the creation of an independent Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox diocese in the United States and the news of the appointment of Father Onufry Kowalsky (the pastor of the Ukrainian parish in Woonsocket, Rhode Island) as pastor in Boston, many parishioners expressed their dissatisfaction with this appointment. They claimed that Father Kowalsky was Polish and a Latinizer, and that he didn’t care for Ukraine or Ukrainian traditions. They pointed out that he had caused dissension in Woonsocket, and that many parishioners there had left the parish, formed a new Ukrainian Orthodox parish, and filed a lawsuit seeking to take over the church building. The Boston group appealed to the new bishop, Constantine Bohachevsky, to rescind Father Kowalsky’s appointment. He refused, and the group took over the church building before Father Kowalsky’s arrival and began to explore their options. When Father Kowalsky came to Boston, he found the church building in the hands of the committee. He had to seek aid from civil authorities to enter it and begin saying regular liturgies. Neither the church committee nor Father Kowalsky were conciliatory, and the parish council called a meeting to discuss alternatives. They again appealed to the chancery in Philadelphia, and they also voted to explore the possibility of joining the new Orthodox diocese. Finally, they filed suit seeking to establish ownership of all the church property. As events unfolded, there was turmoil in the parish community. The largest number of parishioners were disillusioned by the new developments, left the parish, and, for the most part, joined local Latin-rite parishes. At the same time, they also dropped out of organized Ukrainian life. The activists continued with their lawsuit and letter-writing campaign to the chancery, and began to hold religious services on their own without the benefit of clergy. Six families continued to support Father Kowalsky and remained faithful to the Ukrainian Catholic church. After a lengthy legal battle, the court ruled that because the parish had converted into a shareholder society in 1924 with the permission of the administrator of the diocese, the church property belonged to the shareholders, and it ordered a vote of all shareholders be taken to determine what they wanted. The majority voted to retain the property and to become independent of the Ukrainian Catholic diocese. Within a short time, they decided to join the Ukrainian Orthodox diocese. They renamed the parish the Holy Trinity Ukrainian Orthodox parish and Father Basil Kucher became the first pastor. Those who were faithful to the Catholic church and Sacred Heart parish retained the rectory at 363 Beacon Street in Boston and used it for Father Kowalsky’s residence, for Sunday liturgies, and for a Ukrainian school. After a number of years there, the Catholics could no longer pay the mortgage and sold the property with the permission of Bishop Bohachevsky of Philadelphia and Archbishop William Henry O’Connell of Boston. Father Kowalsky was transferred. Before he left Boston, however, Father Kowalsky made a trip to Rome to explain to the Congregation for Oriental Churches what had happened, and on his return brought Papal blessings for the families who had remained loyal.  Sacred Heart Choir, conducted by Helene Sydoriak-Haire in Holy Trinity German Church, July 28, 1950 After the loss of the property and resident priest, religious services for members of the Sacred Heart parish were held several times a year at Holy Trinity German Catholic Church on Shawmut Avenue in Boston. Father Basil Tremba and Father Michael Bobersky came from the parishes in Salem and Fall River, Massachusetts, to conduct liturgies, hear confessions, and perform baptisms and weddings. They were responsible for the ongoing existence of the parish. Parishioners were advised to attend local Latin-rite parishes when Ukrainian services weren’t available. In spite of church-related problems, organized Ukrainian life continued in Boston, and in 1929, Father Joseph Zelechivsky, the pastor of Holy Trinity Church, organized an Orthodox choir which made numerous appearances throughout the New England states and sang on the Yankee Radio Network on a number of occasions. At the same time, the noted Ukrainian ballet master Vasyl Avramenko opened a school in Boston and began to teach Ukrainian folk dancing. A dance group was soon organized, and it quickly became one of the top groups in New England. The Ukrainian community was well organized during the late 1920s and early 1930s, and politically conscious and active. It also followed developments in Europe and supported Ukrainians overseas. When the Soviet occupiers of Eastern Ukraine created a famine in 1932-33 that took the lives of over six million Ukrainians, the Boston community mobilized: in addition to numerous protests, a sorrowful march and services for the dead were held, in which over 6,000 Ukrainians participated. During the 1930s Ukrainians continued to move from their original points of settlement, and soon the West End and Mattapan were home to sizable groups with organizations of their own. In the West End, the Elizabeth Peabody Settlement House acted as a focal point, and a Ukrainian school and Ukrainian Club of Dramatics and Dancing developed there. In Mattapan, Ukrainians purchased a building and converted it into a National Home that acted as the nucleus for the neighborhood. They also set up the Ukrainian-American Citizens and Educational Club. Again a Ukrainian school was established and several other organizations were formed. When World War II broke out, several hundred Ukrainians volunteered for service; they saw duty in all theaters of operation and served in all the armed forces. A number lost their lives and even more received various types of citations. Many civilians helped as best they could, and several women's groups worked with the American Red Cross as well as with the Ukrainian Gold Cross. After the war, great numbers of Ukrainian refugees came to the United States through the port of Boston. Governor Robert Bradford appointed Attorney Anna Chopek as the Ukrainian member of the Displaced Persons Commission to help deal with the new arrivals. The Ukrainian community mobilized its resources and both local parishes organized special Refugee Committees. Sacred Heart Ukrainian Catholic parish formed a committee to welcome refugees; it was affiliated with the National Ukrainian Catholic Refugee Committee and the National Catholic Refugee Committee. TheOrthodox church committee was affiliated with the United Ukrainian American Relief Committee. Among the most active members of both committees were Elias and Maria Chopek, Nicholas Kisil, John and Annie Woloschuk, Sophie David, Peter and Maria Moroz, and William Homan. Danylo Bortnyk, a member of the Orthodox parish, himself sponsored 28 families of refugees. In the mid-1940s, newly ordained Father Gregory H. Tom was sent to Boston as the first resident pastor of the Sacred Heart Ukrainian Catholic parish in more than fifteen years. Upon his arrival in Boston he was taken in by the Elias Chopek family of Mattapan, and he used their home as his residence for the first two years of his service. He immediately began working with active Catholic families and within a short time was able to attract back to the revitalized parish many Ukrainians who had broken with the Catholic church or who had totally abandoned organized Ukrainian life. He sought permission from Archbishop Richard Cushing to expand services at Holy Trinity German Church, and soon weekly liturgies were being said in the lower church, while the parish hall (Casino Hall) and the school were being used for various Ukrainian meetings and events, including annual “sviachene” and “prosphora.” Permission was also received to hold all baptisms, weddings, and funerals in the upper church.  Holy Trinity German Church, Boston, 1942 Archbishop Cushing was very favorably disposed to Father Tom and the Ukrainian parish, and called on both Catholic Action and the Knights of Columbus to aid the parish. Almost fifty young members of Catholic Action volunteered to form a choir to sing at the Sunday liturgy. Helene Sydoriak-Haire became director of the new choir and within a few weeks taught the members how to sing all of the liturgical responses in Old Slavonic. As Father Tom worked on developing the parish, many new immigrants joined, and by 1948 Sacred Heart was again the largest Ukrainian parish in Boston. Father Tom labored unceasingly on behalf of the new arrivals, finding them work, apartments, furniture, and food, and often lending them money. He quickly became known as the "Pastor of the Refugees." His door was always open to those in need.  Bishop John Wright (later Cardinal) attends the first Ukrainian field Mass in Boston, 1948 With the influx of new immigrants, many existing organizations experienced a renaissance and many new ones were formed. The various fraternal associations attracted new members, and branches of the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America and the Ukrainian National Aid Association were established. Both the Ukrainian American Youth Association (SUMA) and Plast (Ukrainian scouts) were formed, new dance groups were launched, and two mandolin orchestras, each with more than thirty members, made their appearance. The parish school flourished and within a few years boasted almost two hundred students. In spite of the hospitality of the German parish, however, parishioners wanted their own place of worship built according to the Ukrainian Byzantine tradition. Fundraising began almost immediately. During the summer, picnics were held every Sunday at the Skalecki family farm on Lafayette Street in Randolph and were usually attended by three to four hundred people. Events were also held at Houghton’s Pond in the Blue Hills and in Casino Hall at the German parish. Drawings for various items were held at least once a month, and every Ukrainian Catholic in Boston always seemed to be selling chances.  Blessing of the land bought for the new Sacred Heart Church, 1951 Funds were collected fairly quickly and Archbishop Richard Cushing gave the parish a gift of $20,000 to help with the effort. Father Tom and several members of the parish committee began to look for land on which to build the new church. After a lengthy search they found several contiguous parcels of land totaling slightly more than nine acres on Forest Hills Street, Jamaica Plain that backed onto Franklin Park, which was the largest park in the city. Father Tom felt that this was an ideal location for a new Ukrainian church because there were large groups of Ukrainian families living nearby in Hyde Park, Roslindale, and Mattapan. Mattapan itself, for example, had more than four hundred Ukrainian families living fairly close to each other and also boasted its own Ukrainian hall. Unfortunately, seven acres of the site comprised the old Ross estate, with its mansion and outbuildings, and had been deeded to the city to be joined to the existing parkland upon the death of the last of the Ross family servants. The grounds themselves were beautiful and boasted many rare and exotic trees and shrubs brought back by members of the family who had been engaged in the China trade. The remaining two acres fronting Forest Hills Street were originally the site of a small private hospital which had to be razed; it had been built over an underground spring and its basement was subject to periodic flooding. After lengthy discussions it became clear that Father Tom had his heart set on the site and was determined to realize his plan in spite of all obstacles. He soon convinced the Boston City Council and the mayor to sell the land to the parish; he then persuaded the state legislature and the governor to agree to the sale, a difficult feat because the site involved parkland.  Archbishop Richard Cushing (later Cardinal) breaking ground for the new Sacred Heart Church, 1952 In 1950, the Ukrainian Catholic parish purchased the land on Forest Hills Street with the proviso that the land could be used only for parochial purposes and that if the parish ever decided to relocate, it would have to sell the land back to the city. The parish could not legally sell it to anyone else. Immediately after the purchase was completed, a multi-stage building program began. Renovations were started on the Ross mansion and it was converted into a rectory and parish center. A large kitchen was installed to handle parish functions; several of the downstairs rooms were converted into a meeting space; a parish office was also installed on the first floor; and several rooms over the kitchen were converted into classrooms. The front part of the second floor was made into a residence for the pastor. Shortly after the work was completed, Father Tom and his mother moved into the rectory. Parishioners gathered regularly in the building, and a dance for the youth of the parish was held in the first-floor meeting rooms every Friday night, with between a hundred to 150 young people in regular attendance. During the summer months special liturgies (“polovi Sluzhby Bozhi”) would be held in the field next to the rectory, and the Roman Catholic archdiocese would always be represented by the archbishop or one of the auxiliary bishops, as well as a contingent of the Knights of Columbus. For a number of winters large ice crosses were set up on the site of the church building on Yordan, and water was blessed out of doors.  Field Mass, July 16, 1950 A decision was made to site the new church building adjacent to Forest Hills Street where the hospital had been located. Plans were drawn up for a building that had a parish hall on the ground level and the church on a second level above it. There was to be one main dome over the center of the façade. Access to the church would be through a grand archway (topped with a mosaic of the Sacred Heart) which would lead into the hall and two staircases on either side which would lead to the church itself. Immediately after construction began, the underground spring again became active, and the contractor had to search for a solution to stem the continuing flow of water threatening to flood the excavated site and the poured foundations. Eventually a system of pumps was installed that worked twenty-four hours a day to channel the water away from the site and into the sewer system. Once this issue was resolved, a basement was built of cinder blocks. Unfortunately, the water problem exhausted the building fund; it was resolved not to drive the parish into debt by seeking a large mortgage, but to temporarily roof-over the basement hall and use it as the church until more money could be raised. A new building fund was created and for a period of time, a second collection was taken every Sunday to keep up the momentum of fundraising to complete construction. Sadly, disagreements began to surface among parishioners. Relations between those who had come to Boston before World War I and those who had come as refugees after World War II became strained. There were difficulties over the use of the kitchen, the control of the parish funds, and the question of the liturgical calendar. The parish in Boston had voted as early as 1924 to follow the “new” Gregorian calendar, and the Ukrainian diocese of the United States eventually followed suit, mandating that all Ukrainian-rite churches in the United States follow the Gregorian calendar. Within a short time all grievances were subsumed into a demand for the introduction of the “old” Julian calendar for all liturgical services in the parish. Letters were written to the chancery in Philadelphia, and a number of priests were dispatched to Boston to listen carefully to everyone’s opinion. Because of the parish’s earlier history, the chancery was determined not to make the same mistake twice. A recommendation was made to allow the formation of a second parish, and a dispensation was granted for it to follow the Julian calendar. Ironically, when the second group was created, the divisions really made little sense. There were “former” settlers and newcomers in each group. For a time Boston was the only Ukrainian parish in the country celebrating two calendars simultaneously, and it was also the only parish with a group following the Julian calendar. Ultimately Sacred Heart retained the Gregorian calendar and the new group espoused the Julian calendar. As the new parish began to take shape, priests were sent by the chancery to minister to it. For a time Father Tom would say one liturgy for the group that was staying with the “new” calendar and Sacred Heart parish, and then the visiting priest would say a separate liturgy for the second group following the Julian calendar. Both liturgies were held in the basement church on Forest Hills Street. In 1952, a Julian-calendar parish was officially established with Father Dmytro Fedasiuk as its first pastor. St. George’s Syrian Orthodox Church on Tyler Street in Chinatown was soon purchased, and the parish decided to keep its name because it was also the name of the cathedral in Lviv. The property had a large hall in the basement and a church above it. Father Fedasiuk remained with the parish only a short time and was replaced by Father Wolodymyr Kozoriz.  St. George’s Church A residence for the new pastor was procured in an apartment building across the street from the church. Shortly after moving into the new building, the parishioners of St. George’s renovated the church interior, had the iconostas repainted and gilded, installed new benches, and had the exterior sandblasted. They also restored and refurbished the church hall. The parish continued to develop and thrive until the early 1960s, when the Commonwealth of Massachusetts announced that it was going to construct an extension to the Massachusetts Turnpike to connect it with the main expressway in the city. Unfortunately, the highway was planned through the area where St. George’s was located, and the state took the property by eminent domain. After lengthy negotiations, the state agreed to give the parish $100,000 for the land and building. When the parish finally left the premises because the state was demolishing them, the ordinary of the Ukrainian Catholic diocese of Stanford, Connecticut (established in 1958), Bishop Joseph Schmondiuk ordered the parishioners of St. George’s to return to Sacred Heart in Jamaica Plain. Citing a shortage of priests, Bishop Schmondiuk withdrew the pastor but stipulated that the move could be temporary and that he would try to make other arrangements eventually. Faced with the bishop’s mandate, a number of parishioners returned to Sacred Heart. However, the majority refused and began to attend services as a group at Holy Trinity German Catholic Church, which was only a few blocks from St. George’s. Eventually this group fragmented: some began to attend liturgy at Our Lady of Kazan Russian Catholic mission in South Boston and others at Our Lady of Czestochowa Polish Catholic parish in South Boston; still others attended St. Andrew’s Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Forest Hills or local Latin-rite Catholic parishes; a few stopped going altogether.  Iconostas at St. George’s Church Because St. George’s parish had incorporated itself in the state of Massachusetts, parishioners argued that the funds from the church should come to them as the corporation and not go to the bishop’s chancery. They were able to convince the state, and with the money from the sale they purchased a residential building on Beech Street in Roslindale which they converted into a hall and parish center. Life at Sacred Heart parish in Jamaica Plain continued much the same after the departure of the group that founded St. George’s. Plans were never abandoned to finish the church structure and the building fund collections continued. Improvements continued to be made to the parish property. One of the old buildings was razed, the outdoor stage was rebuilt, the rectory was again completely renovated, as was the kitchen, utilities were upgraded, and new siding was put on the building. Finally, the driveway was regraded and a new roadway to the rectory was constructed.  A Christening at St. George's by Fr. V. Kozoriz, 1950s The parish continued its school and religious education program, and in the mid-sixties formed a youth group with more than seventy members under the tutelage of seminarian Daniel O’Leary. It also invited the Sisters of St. Basil the Great to conduct special summer religious-education programs. As a result of this activity, two vocations to the priesthood were fostered. Each pastor of Sacred Heart continued to reach out to the former parishioners of St. George\’s, and finally a new pastor, Father Stephen Chomko, began a series of negotiations in 1968 that culminated in the merger of Sacred Heart with St. George's. A formal agreement was drawn up and ratified by both groups; Father Chomko and the two church committees then went to the bishop\’s chancery in Stamford to sign the accord. In order to guarantee harmony, both sides agreed to give up the names of their parishes and Bishop Schmondiuk then named the new entity Christ the King parish. It was agreed that the parish would officially follow the Julian calendar, but that the rights of those who wished to follow the Gregorian calendar would not be restricted in any way and that the parish would hold services for all major religious holidays according to both calendars. Christ the King was the only parish in the United States at that time to be officially bi-calendar. Additionally, the parishioners of St. George’s agreed to sell the property on Beech Street and put the money into a joint building fund. Within a year enough funds had been raised to warrant the construction of a new church. It was decided not to complete the church on top of the standing hall, but to choose a new site on the hill next to the rectory. Construction began in the fall of 1971, and a new modernistic 400-seat structure incorporating many Ukrainian architectural elements was dedicated in the spring of 1972. Interestingly, the money in the building fund covered the construction costs completely, and the united parish was able to move into the new church without accruing any debt. The tempo of parish life accelerated and new parish-based organizations continued to appear, including branches of the Ukrainian Encyclopedia Society, Women for the Defense of the Four Freedoms of Ukraine, the Ukrainian Society of Engineers, the Ukrainian Fraternal Federal Credit Union, the Ukrainian-American Veterans, and the Ukrainian American Women's League.  Massachusetts Governor Edward J. King signs a Ukrainian Independence Proclamation - present are community leaders and Fr. P. Ohirko (Christ the King Church) and Fr. M. Pacholok (St. Andrew Orthodox Church), early 1980 As the Soviet Union weakened and began to relax some of its strict controls, visitors began coming to the parish from Ukraine, and with independence new immigrants came to the city for the first time in fifty years. In the sixteen years of Ukrainian independence more than five thousand Ukrainians have settled in Boston and a fair number of them have joined Christ the King parish. As a result of this infusion, the parish has again been revitalized and its complexion has changed dramatically. Although the parish has an official record of one hundred years as an ecclesiastical entity in the city of Boston, with an additional pre-history of almost twenty years, it is now predominantly comprised of people who were born in Ukraine and who are only beginning the process of acculturation. In a sense, in its hundredth year Christ the King Ukrainian Catholic parish is more Ukrainian than it has been over the last ninety years. The parish has a long history of service and an enviable record of accomplishment. It has helped a number of generations of Ukrainians maintain their religious and cultural identity and is hard at work doing so yet again. In its long history Christ the King Ukrainian Catholic parish has produced solid citizens and has managed to add a bit of color to the vibrant mosaic that is Boston. Peter T. Woloschuk, Boston, 1976, Revised and expanded, 2007  Annual meeting in Sacred Heart Church Hall, early 1970s  Children singing “Hahilky” during Easter at St. George’s Church, 1950s |